You know, it’s fascinating how a simple movie title can spark such a firestorm in Nigeria, where faith runs deep in everyday life and entertainment often walks a tightrope between creativity and cultural norms. The latest uproar centers on Ini Edo’s new film, A Very Dirty Christmas, which has drawn sharp criticism from the Christian Association of Nigeria, or CAN as most folks call it. They labeled the title offensive and disrespectful to the Christian faith, urging the producers to rethink it and even apologize publicly. This isn’t just some passing comment; it’s stirred up debates across social media, with some defending artistic freedom and others rallying behind religious sensitivities. But let’s dig deeper here, because this isn’t an isolated incident. It raises bigger questions about whether Nollywood filmmakers are deliberately courting controversy through provocative titles to boost their marketing; what some might call ragebaiting; or if religious groups are growing increasingly vigilant, perhaps even oversensitive, in protecting what they see as sacred. And to put it in perspective, we’ll look back at similar clashes, like the one surrounding Gangs of Lagos, which tangled with cultural rather than strictly religious issues but shares some parallels in how entertainment clashes with community values.

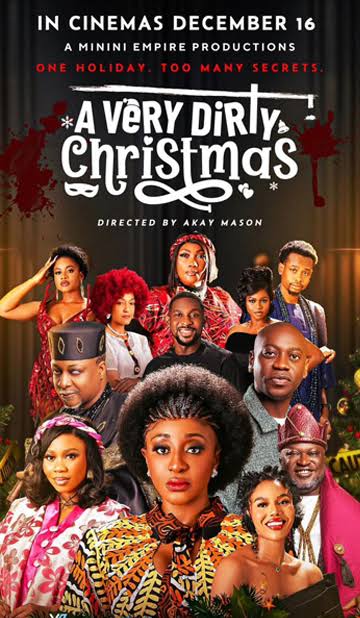

A Very Dirty Christmas

First off, let’s lay out what happened with A Very Dirty Christmas. The film, produced by Ini Edo, who’s no stranger to Nollywood stardom with her roles in everything from romantic dramas to thrillers, was set for release around the holiday season. It’s described as a family comedy that dives into the chaos of holiday gatherings; think messy relationships, hidden secrets, and the kind of drama that unfolds when relatives cram under one roof. But the title; that’s where the trouble started. CAN issued a statement expressing deep concern, saying the movie title, ‘A very Dirty Christmas’ trivializes the holy celebration of Christ’s birth. They pointed out that Christmas represents purity and joy for Christians worldwide, and slapping “dirty” onto it feels like a slap in the face. In their words, it’s not just about the word itself but how it could erode respect for religious traditions in a country where Christianity holds sway for millions. A report from Punch Newspapers captured this sentiment clearly, noting that CAN found the title troubling amid efforts to maintain moral standards in media. They even called on regulatory bodies like the National Film and Video Censors Board, or NFVCB, to step in and possibly pull the film if changes weren’t made.

Ini Edo didn’t stay silent for long. She took to social media and interviews to clarify her intentions, emphasizing that she’s a Christian herself and would never aim to dishonor her faith. In a heartfelt response, she explained that “dirty” here refers to the figurative mess of family scandals and reconciliations, not anything literal or blasphemous. She apologized for any unintended offense but stood by the creative choice, saying the film actually promotes themes of forgiveness and love; core Christian values, ironically enough. Recall, NOLLYWOOD LIFE reported her breaking her silence on the matter, where she stressed that the title was meant to be catchy and relatable, drawing from real-life holiday experiences that aren’t always picture-perfect. Her fiancé, actor IK Ogbonna, jumped in to defend her too, questioning why CAN waited until after the film’s approval and promotion to raise alarms. He argued in a Punch interview that the board had already greenlit it, so the objection felt untimely and perhaps unfair. Even the NFVCB weighed in, reaffirming their commitment to religious sensitivity while noting they’d engaged with the producers and approved the title after review. A Premium Times piece detailed how they hadn’t received a formal complaint from CAN but were open to dialogue, highlighting their role in balancing creativity with cultural respect.

Now, this begs the question; is Nollywood leaning into these kinds of titles as a marketing ploy? In an industry that’s exploded globally thanks to streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime, standing out is everything. Films need buzz, and sometimes that means poking at sensitive spots to get people talking. This tactic, often dubbed ragebaiting in marketing circles, involves creating content that deliberately stirs anger or outrage to drive engagement; shares, comments, debates that all amplify visibility. A BBC article from last year explained how it works on social media, where inflammatory posts can go viral by tapping into emotional triggers. Apply that to films, and you see patterns; a provocative title generates headlines, free publicity from critics, and curiosity from audiences who want to see what the fuss is about. Think about it; without the CAN backlash, would A Very Dirty Christmas have trended as much? Probably not. It’s similar to how some Hollywood films use shock value in trailers or posters to hook viewers, but in Nigeria’s context, where religion is intertwined with daily life, it hits harder.

But is this intentional on Nollywood’s part? Some insiders say yes. Producers know that in a crowded market, controversy sells tickets; or in this streaming era, views. Take the backlash itself; social media exploded with discussions, from Facebook groups debating religious intolerance to Instagram reels breaking down the issue. One viral reel questioned why CAN was upset when terms like “dirty December” (slang for wild holiday partying) have been around for years without much fuss. Edo herself might not have set out to ragebait, but the outcome fits the bill. And it’s not unique to her; Nollywood has a history of titles that push boundaries, like those exploring taboo topics such as infidelity, witchcraft, or social vices, often drawing fire from conservative quarters. A study in the Journal of Religion and Human Rights, available as a PDF, discusses how Nollywood films sometimes propagate religious doctrines but can also challenge them, leading to negative perceptions when they veer into sensitive territory. The industry’s growth means more risks; filmmakers experiment to appeal to younger, global audiences who crave edgier content, but that clashes with local expectations.

On the flip side, maybe religious bodies aren’t being oversensitive; perhaps they’re rightfully guarding against what they see as cultural erosion. Nigeria is a deeply religious nation, with Christianity and Islam dominating, and entertainment often reflects or influences societal morals. CAN’s reaction stems from a broader concern about secular influences diluting faith; especially during holidays like Christmas, which for many is a time of spiritual reflection, not commercialization or mockery. Leadership Newspaper reported CAN demanding an apology, arguing the title undermines the sanctity of the season. And they’re not alone; Muslim groups like MURIC have similarly protested films they deem Islamophobic or stereotypical. For instance, MURIC once kicked against a movie for portraying Muslims negatively, as noted in a Facebook post amid wider discussions. This sensitivity isn’t new; it’s rooted in Nigeria’s history of religious tensions, where media can either bridge divides or inflame them. A Guardian article on NFVCB’s stance underscores this, noting the board’s push for responsible regulation to avoid offending faiths.

To really understand this tension, let’s compare it to past controversies. Take Gangs of Lagos, released a couple of years back on Amazon Prime. Directed by Jade Osiberu, it’s a gritty crime drama set in Lagos Island, exploring gang life and political intrigue. But the film drew massive backlash for depicting the Eyo masquerade; a sacred Yoruba cultural icon; as associated with thuggery. The Lagos State Government, through its tourism ministry, condemned it as cultural misrepresentation, saying it portrayed the Eyo in a grotesque light that dishonored traditions. Premium Times covered the outcry from Isale Eko unions and officials, who felt it mocked their heritage. The controversy escalated to court, where in early 2025, a judge ordered the producers to apologize publicly for misappropriation. This Day Live reported the ruling, highlighting how it forced Amazon and the team to issue statements regretting any offense. While not directly religious, the Eyo has spiritual elements tied to Yoruba beliefs, blending culture and faith in ways that mirror CAN’s concerns with Christmas.

The parallels are striking. In both cases, filmmakers aimed for authenticity or edginess; Gangs of Lagos drew from real urban struggles, much like A Very Dirty Christmas pulls from family dynamics. But critics saw sacrilege. For Gangs, the Oba of Lagos slammed it for violating Eyo legacy, per Vanguard reports. Social media reactions were mixed; some praised the film’s boldness in exposing societal ills, while others decried it as insensitive. Punch analyzed the subversive politics behind it, noting how A very dirty Christmas movie challenged power structures but alienated communities. Similarly, with Edo’s film, defenders argue it’s just entertainment, not an attack on faith. Yet the outcry led to apologies and regulatory scrutiny, showing how quickly these disputes can escalate.

Broadening out, Nollywood’s run-ins with religious bodies aren’t rare. Remember the flap over films like The Wedding Party or even older ones accused of promoting occultism? Groups have protested titles or plots that touch on witchcraft, which some see as anti-Christian. A Facebook group discussion on a recent film sparking intolerance debates pointed to growing polarization, where every creative choice is scrutinized through a religious lens. And it’s not just Christians; Islamic sensitivities come into play too. Events Cloud reported an actress criticizing stereotypes of Muslim women in media, calling for more authentic portrayals. This reflects Nigeria’s diverse fabric, where entertainment must navigate multiple faiths without alienating any.

So, what’s the root cause? Part of it is Nollywood’s evolution. Once dominated by low-budget videos, it’s now a billion-dollar industry with international reach. Filmmakers like Edo push boundaries to compete globally, inspired by Hollywood’s irreverence. But Nigeria’s audience is different; religion isn’t just personal, it’s communal. A Legit.ng piece on the A very dirty Christmas captured public divides, with some questioning if titles alone warrant such fury. Meanwhile, religious leaders feel duty-bound to speak up, especially in an era of social media where offenses spread fast. My Joy Online quoted CAN urging sensitivity during festive times.

From a marketing angle, ragebaiting might be at play, even if unintentional. Econlib’s economics take explains how content that angers drives engagement, turning controversy into profit. Films like Joker or even Disney remakes have faced similar accusations; Reddit threads discuss racebaiting in media to stir debates. In Nollywood, it could be a survival tactic; generate talk, get streams. But at what cost? Manifest Media warns that while it sells, it risks backlash and boycotts.

(And here’s where I pause to reflect; as someone who’s watched Nollywood grow, I see both sides. Creativity shouldn’t be stifled, but respect matters in a society where faith anchors people amid chaos.)

Looking ahead, these tensions could shape regulations. NFVCB’s involvement in Edo’s case, as Vanguard detailed, shows they’re mediating more actively. Perhaps guidelines on titles touching religion could emerge, but that risks censorship. For filmmakers, it might mean consulting communities earlier; for religious groups, dialogue over demands.

A Very Dirty Christmas

In the end, this “title scandal” highlights a deeper rift; between a thriving creative industry and a vigilant religious sphere. Is Nollywood ragebaiting? Sometimes, yes, for visibility. Are religious bodies too sensitive? Maybe, but their concerns stem from genuine protectiveness. Like Gangs of Lagos, which settled with an apology, these clashes often end in compromise. But as Nollywood expands, finding balance will be key to avoiding more scandals. After all, entertainment thrives on stories that resonate, not divide.