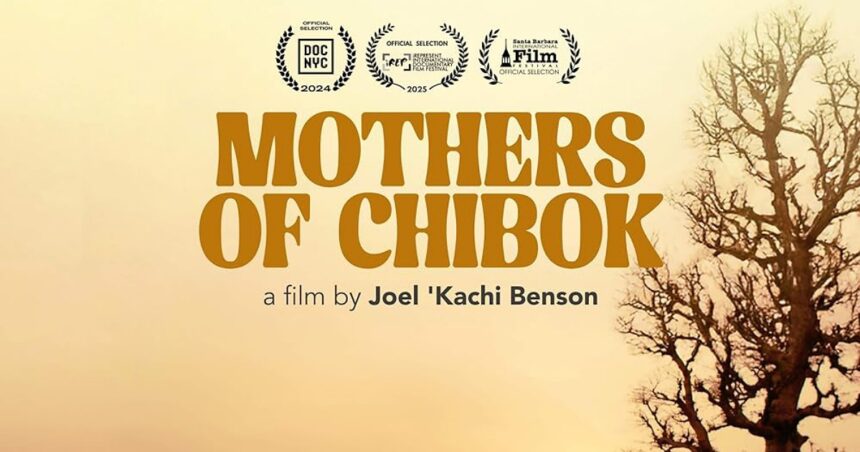

People talk about films that change how we see the world. Mothers of Chibok does that in a direct way. This documentary by Joel Kachi Benson looks at the lives of four mothers in a Nigerian village years after their daughters got taken by Boko Haram. It came out in 2024 but hits cinemas on February 27, 2026. That’s 12 years since the Chibok kidnapping in 2014, when 276 girls got abducted from their school. The film follows these women as they farm to support their families and push for education for their other kids. It shows their daily fight in a place where loss is part of life.

Documentary: Mothers of Chibok

Benson started this journey with his earlier work, Daughters of Chibok, a VR short that won the Best VR Story at the Venice Film Festival in 2019. That one focused on the pain right after the event. Now, Mothers of Chibok picks up later, showing what happens when the news moves on but the hurt stays. Critics call it a story of courage and hope, not just sadness. In 2026, with school abductions still happening in Nigeria, this film matters more than ever. Over 1,500 kids have been taken since Chibok, and many from that group are still missing. Around 82 girls from Chibok remain captive as of recent reports. The film reminds us that these events are not old news; they shape lives today.

The Chibok story started on April 14, 2014. Boko Haram raided a school in Borno state and took the girls. It got global attention, with campaigns like Bring Back Our Girls. Some girls escaped or got released over time, but many did not. By 2024, ten years later, the number of missing was still high, and families kept waiting. In 2025, more abductions happened, like 25 girls from a school in Kebbi state and over 300 students from another in Niger state. These attacks echo Chibok, showing the problem has not gone away. Nigeria’s government has tried rescues, but insecurity in the north keeps it going. The United Nations called for better protection of kids after these events. Mothers of Chibok steps in here, giving a voice to those left behind.

Joel Kachi Benson is the man behind the camera. He is a Nigerian filmmaker who uses both regular film and VR to tell stories from Africa. His first big hit was Daughters of Chibok, which put viewers right in the homes of affected families. It won at Venice because it made people feel the absence of the girls. Benson trained in Britain and the US, but he focuses on Nigeria. He says he wants to show the full picture of these women, not just as victims, but as people who keep going. For Mothers of Chibok, he spent time in the village over a farming season. The film has producers like Jamie Patricof and Joke Silva, a big name in Nollywood. It runs 88 minutes and paints a clear view of life after tragedy.

The story centers on four mothers: Yana Galang, Ladi Lawan Zanna, Maryam Ali Maiyanga, and Lydia Yanna. They grieve for their missing daughters but work hard to educate their other children. The film marks the 10th anniversary of the abduction, but by 2026 release, it’s 12 years. We see them farming, dealing with poverty, and facing silence from the system. One review calls it an elegy for a wounded nation, where women face rape, loss, and betrayal with dignity. Benson shifts the focus from the girls to the mothers who stay and rebuild. It’s not about the terrorists; it’s about survival.

Filmmakers have a big role when they tell real stories like this. Benson sees his work as a historical record. He captures moments that might get forgotten otherwise. In a world where news cycles move fast, documentaries hold the truth steady. This film uses real grief to show what scripted movies often fake. Silence plays a key part; long shots of the women working or sitting quietly say more than words. It’s not dramatic like a Hollywood film; it’s raw. That makes it stronger. Benson’s responsibility is to tell it honestly, without adding fluff. He lets the mothers speak for themselves, showing their strength in simple acts like planting crops or sending kids to school.

This approach outshines scripted dramas because it’s true. In movies, actors play sad roles, but here, the pain is real. One mother talks about living with the absence every day. The film avoids big speeches; instead, it shows quiet moments of hope. Benson said he wanted the world to see these women as warriors, not victims. That’s the power. Scripted films might add music or twists to keep viewers hooked, but this one relies on life itself. And life, in Chibok, is full of unspoken hurt that hits harder.

Social impact is the keyword here. Mothers of Chibok acts as resistance. These women resist by living on, farming, and educating kids despite everything. The film brings attention back to Chibok, where over 100 girls were still missing in 2021, and the number has not dropped much. By showing this, Benson pushes for change. Documentaries like this can spark talks on governance, security, and women’s rights in Nigeria. At festivals, people discuss how it exposes poverty and betrayal. The social side comes from making viewers care again. In 2026, with new abductions like the 24 girls released in Kebbi, the film ties past to present. It calls for better protection of schools and kids.

The festival run builds the hype. Mothers of Chibok had its world premiere at DOC NYC in 2024. That’s America’s biggest documentary festival. There, it got Q&A sessions with Benson, and critics praised its timely story. Then, it opened the iREP International Documentary Film Festival in Lagos in March 2026. iREP is a key spot for African docs, and this year it’s at the Ecobank Pan African Centre. The theme is Transformation, which fits the film’s message of change through endurance. Over 30 films show there, but Mothers of Chibok stands out for its local roots. Sites like What Kept Me Up and Pulse have early reviews calling it a must-watch. This early buzz comes from insiders who saw it at festivals.

As a sequel, people compare it to Daughters of Chibok. The VR short was short and immersive, putting you in the pain. Mothers of Chibok is longer, 88 minutes, and follows a season of life. Does it add value? Yes, because it shows time passing. The first one captured fresh grief; this one shows ongoing struggle. Reviews say it expands the vision, turning short glimpses into a full portrait. Benson returns to the same community, so it’s a true follow-up. That adds depth, asking if things got better. Spoiler: Not enough.

Why write a preview now? The cinema release is February 27, 2026, in Nigeria and Ghana. Before the rush, this article says why you must see it. It’s distributed by FilmOne, a big step for Nigerian docs, which often go online or to events. Seeing it on the big screen makes the silence and grief bigger. Plus, it’s a chance to support stories that resist forgetting. In 2026, with abductions like the 303 students in Niger state, the film warns us to act. Don’t wait for reviews; go in knowing it’s important.

Benson’s responsibility shines through. He could have made a sensational film, but he chose quiet truth. That’s why it outshines dramas. Real grief does not need scripts; it needs a camera to record it. The mothers’ silence speaks volumes about loss and strength. One review notes how it digs into Nigeria’s reality: poverty, survival, and the cost of silence. This makes the film a tool for social change. It resists by remembering.

The impact goes beyond the screen. At iREP, there’s a mobile phone filmmaking workshop before the festival. That teaches new storytellers, spreading the resistance. Benson’s work inspires others to document their truths. In a country where over 7,000 women and girls got abducted since 2009, films like this push for justice. Social media buzz, like posts on X about the trailer, shows people are talking. One user roots for it, another plans to see it in cinemas.

Comparing to Daughters, the new film adds layers. The VR was about immediate absence; this is about long-term hope. It ends on new beginnings, showing talent in Benson’s work. That’s value added. Festivals agree, with selections and premieres.

In the end, Mothers of Chibok is 2026’s key film because it records history while resisting erasure. Benson handles his role with care, using silence to amplify grief. The social impact? It renews calls for action on abductions. See it in February; it’s more than a movie.