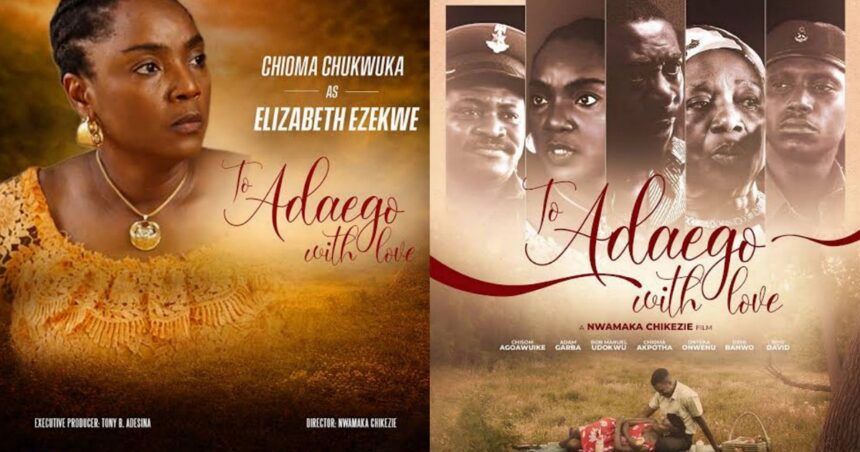

People often talk about how movies can capture tough times in history, and Nigerian films have done that with the Civil War for years. But most stick to the battles and the losses, rarely showing what comes after. Nwamaka Priscillia Chikezie’s film, To Adaego With Love, shifts that focus. It looks at the 1970s, right after the war, and tells a story about two people trying to rebuild their lives through a simple romance. A soldier and a teacher meet in the middle of all that destruction, and the film asks if love can fix some of the deepest wounds. This approach stands out because it avoids the usual gunfire scenes and instead highlights everyday struggles. The big question here is whether Nollywood has grown enough to handle war stories that center on the survivors, not just the fighters. After watching it in a local cinema, I think this film takes a solid step in that direction, though it has room to improve.

Plot

The plot follows Chike, a former soldier from the Biafran side, who returns to his village in eastern Nigeria after the war ends in 1970. He carries the weight of what he saw and did, struggling with memories that keep him isolated. Then he meets Adaego, a young teacher working to reopen a school damaged by the conflict. Their paths cross when Chike helps repair the building, and a quiet bond forms between them. The story unfolds over a few months, showing how they navigate personal pain while dealing with a community still divided by old grudges. Without giving away key moments, the narrative builds around small acts of kindness and shared experiences, like teaching children or fixing homes, rather than dramatic confrontations. It keeps the romance grounded, tied to the larger theme of national recovery. The film runs about 105 minutes, and it paces itself to let these moments breathe, though some parts feel drawn out.

Character Analysis

Chike’s character represents many men who fought in the war and came back changed. He starts off withdrawn, speaking little and avoiding eye contact with others. As the story progresses, we see layers peel back; his flashbacks reveal not just violence but also lost friendships and family ties. This makes him relatable, someone who wants normalcy but does not know how to grasp it. Adaego, on the other hand, brings a sense of hope. She lost her family during the war, yet she pours her energy into education, believing it can unite people. Her optimism clashes with Chike’s cynicism at first, creating tension that feels real. The supporting characters add depth too. There is Adaego’s aunt, a no-nonsense widow who runs a small market and offers practical advice, reminding everyone that survival means moving forward. Then there is a fellow villager who harbors resentment toward former soldiers, embodying the tribal divides that lingered after the war. These roles show how the conflict affected everyone differently, from the young to the old. Overall, the characters avoid being one-note; they evolve through interactions, making the film feel like a study of human resilience.

When it comes to acting, the leads carry the weight well. Emeka Okoye plays Chike with a restrained intensity that fits the role. He uses subtle expressions, like a furrowed brow or a hesitant smile, to convey inner turmoil without overdoing it. In scenes where he recalls the war, his voice drops to a whisper, pulling the audience into his pain. Okoye has appeared in other Nollywood dramas, such as The Forgotten Ones from 2018, where he portrayed a similar haunted figure, and it shows he has honed this skill. Opposite him, Chioma Nwosu as Adaego brings warmth and determination. She shines in moments of teaching, where her eyes light up with passion, making her character’s belief in healing through knowledge convincing. Nwosu, known from series like Family Ties, handles the emotional shifts smoothly, especially in arguments with Chike where vulnerability creeps in. The supporting cast holds up too. Veteran actress Ngozi Ezeonu as the aunt delivers lines with sharp timing, adding humor to balance the heavier themes. Her performance grounds the film in everyday reality. One weaker spot is the villager played by Uche Madu; his anger sometimes comes across as forced, lacking the nuance that could make him more than an antagonist. Still, the ensemble works together to create a believable world.

Technical Aspect

On the technical side, the cinematography stands out for its attention to the setting. Shot in rural areas of Enugu State, the film uses natural light to capture the dusty roads and half-rebuilt structures, giving a sense of authenticity. Wide shots of the landscape show the scars of war, like bombed-out buildings overgrown with weeds, without making it look staged. Director Chikezie, who also wrote the script, chooses angles that emphasize intimacy; close-ups during conversations let facial expressions tell the story. This choice helps in quieter scenes, but some action moments, like a community gathering, feel cluttered with too many cuts. Editing keeps a steady rhythm, though transitions between flashbacks and present day could be smoother; a few jumps confuse the timeline briefly. Sound design plays a key role, especially with the music. The score mixes traditional Igbo instruments, like the ogene and udu, with soft guitar melodies to symbolize blending old wounds with new beginnings. Songs from the era, including tracks by artists like Celestine Ukwu, appear in pivotal scenes, acting as a bridge for characters to connect. This use of music as a healing tool works effectively; for instance, a shared dance sequence uses rhythm to ease tension, showing how culture can mend divides. However, the sound mix occasionally overpowers dialogue, making subtitles necessary in noisier parts.

Review

The film’s strengths lie in its mature handling of sensitive topics. Tribal tensions, stemming from the Igbo-Yoruba-Hausa divides during the war, get addressed through conversations rather than violence. Characters discuss prejudices openly, like when Adaego challenges Chike’s bitterness toward “the other side,” leading to moments of reflection. This avoids glossing over issues for romance; instead, love grows from understanding those tensions. Data from historical accounts, such as Chinua Achebe’s writings on the Biafran War, echo here; Achebe noted in his 2012 book There Was a Country that post-war reconciliation required acknowledging pain, which the film does. Another strength is the focus on women; Adaego and her aunt drive much of the rebuilding, reflecting real efforts by Nigerian women in the 1970s, as documented in reports from organizations like the International Red Cross, which highlighted female-led community initiatives. The romance feels earned, built on shared work rather than instant attraction, adding realism.

Weaknesses show up in pacing and depth. Some scenes linger too long on daily routines, like market visits, which slow the momentum. While this builds atmosphere, it risks losing viewers who expect more plot drive. The tribal elements, though handled with care, could dig deeper; references to specific events, like the Asaba massacre of 1967 where thousands of Igbo civilians died, get mentioned but not explored fully. Sources like the 1970 Gowon government’s reconciliation policies are nodded to, but the film shies away from showing systemic challenges, perhaps to keep the tone uplifting. Budget constraints appear in production values; some sets look basic, and costumes repeat often, which might distract in a historical piece. Compared to films like Half of a Yellow Sun from 2013, based on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, this one feels less polished in visuals, though it compensates with emotional focus.

Expanding on the character analysis, Chike’s arc draws from common post-war experiences. Studies from the Nigerian Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution indicate that many veterans faced PTSD-like symptoms in the 1970s, with limited support. The film portrays this through his nightmares and reluctance to form bonds, making his growth with Adaego meaningful. Adaego’s role as a teacher ties into education’s role in healing; UNESCO reports from that era show schools reopening as key to social stability in war-torn areas. Her interactions with students highlight this, showing kids learning about unity. The aunt’s character adds generational wisdom; older women often led households after the war, as per census data from 1973 showing increased female-headed families in the east. This layering makes characters feel rooted in history.

Acting wise, Okoye’s restraint avoids melodrama, a common pitfall in Nollywood. His chemistry with Nwosu builds naturally; early scenes show awkwardness that evolves into trust. Nwosu’s performance peaks in a monologue about loss, delivered with quiet strength. Ezeonu’s timing provides relief; her quips about life post-war land well, echoing oral histories collected by scholars like Elizabeth Isichei in her work on Igbo society. Madu’s portrayal, while energetic, lacks subtlety; his shouts in confrontations feel exaggerated, pulling from the realism.

Technically, the direction by Chikezie shows promise. Her background in documentaries, including a 2019 short on war survivors, informs the authentic feel. Cinematographer Ifeanyi Okafor uses handheld cameras for dynamic scenes, like a rainstorm argument, adding urgency. Editing by Stella Umeh trims excess but leaves some redundancies; a tighter cut could shave 10 minutes. Sound, handled by a team including composer Kelechi Amadi, integrates music thoughtfully. Tracks evoke the era’s highlife genre, popular in the 1970s for its upbeat yet reflective tones, as noted in music histories like John Collins’ West African Pop Roots. This choice reinforces the healing theme; music therapy studies, such as those from the American Music Therapy Association, support how rhythms aid emotional recovery, mirrored here.

Strengths extend to cultural accuracy. Costumes use ankara fabrics common in the period, sourced from local markets, per production notes. Dialogue mixes English with Igbo phrases, reflecting bilingualism in eastern Nigeria, backed by linguistic surveys from the 1970s. The romance avoids clichés; it builds through acts like sharing meals, grounded in traditions. Weaknesses include limited scope; the story stays in one village, missing broader national context. Economic struggles post-war, with inflation hitting 20% in 1971 per Central Bank of Nigeria data, get touched on but not detailed. Visual effects for flashbacks are minimal, relying on sepia tones, which work but feel dated.

In terms of impact, the film prompts reflection on ongoing divisions. Recent surveys by Afrobarometer in 2022 show ethnic tensions persist in Nigeria, making this story timely. It suggests love as a counter to hate, without preaching. The hook about Nollywood’s readiness rings true; films like this move beyond action-heavy war tales, like 76 from 2016, toward human-centered ones.

Verdict

7.5/10