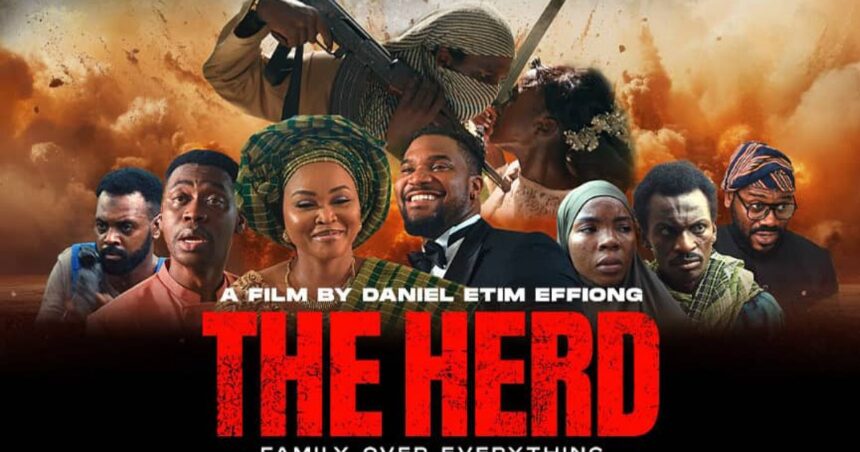

Watching The Herd on Netflix felt like sitting through something that’s way too close to what we hear on the news every day in Nigeria. Daniel Etim Effiong steps behind the camera for his first full-length film here, and he doesn’t hold back; he dives straight into the mess of insecurity, kidnappings, and all those ransom nightmares that have become part of life for so many people. The story kicks off with a wedding full of joy, friends laughing, family dancing… and then bam, everything flips when a group heading back gets ambushed by armed guys posing as cattle herders. From there, it’s all about survival, desperation, and those ugly truths bubbling up about how divided the country really is.

But honestly, the real punch of this movie isn’t in retelling the ambush or the chase for ransom; plenty of us already know those stories too well. What hits harder is how it stirred up so much argument online and offline, especially around how it shows different ethnic groups. A lot of folks, particularly from the north, got upset right away, saying it paints Fulani herders as the bad guys, linking them straight to bandits and terrorists. And yeah, that opening scene where the cattle cross the road and suddenly guns come out… it does feel direct, almost too blunt. Some people called for boycotts, even deleting Netflix over it, arguing it fuels stereotypes and could make tensions worse in a place already on edge.

On the flip side, the director has pushed back, saying it’s more complicated than that. He points out that the film shows Fulani folks as victims too; bandits stealing their cattle to use as cover. And the criminals aren’t just one group; there are Yoruba characters tipping off the gang, a pastor deep in organ trafficking, even touches on the Osu caste thing among Igbo families that causes its own kind of pain. It’s like the movie is trying to say evil and corruption cut across everywhere, not pinned to one tribe or religion. But did that nuance come through for everyone? Clearly not, because the backlash was loud and fast. I think part of the problem is how raw the issue still is; banditry and herder-farmer clashes have claimed so many lives, displaced communities, and no one’s really fixed it. So when a film throws it on screen, even fictionally, it feels like poking an open wound.

Nigeria

Is it fair to ask if the filmmakers were careful enough with those portrayals? They consulted people, did research, or so Effiong says in interviews. Yet some scenes, like the kidnappers speaking Hausa, dressed in that herder style, dominating the violence… those stick in your mind, and for viewers already sensitive, it overshadows the broader point. One particular moment that got a lot of heat is the ambush itself; it’s chaotic, brutal, no glamour, just sudden terror. Then later, inside the gang, you see infighting, a leader trying to go independent, even some humanity in smaller roles. But the initial image sets the tone, and maybe that’s where it risks reinforcing what people fear rather than challenging it. Another arc that stirred talk is the church subplot; a respected pastor (played chillingly by Lateef Adedimeji) tied to harvesting organs from victims. That drew comparisons to how Nollywood has long shown Igbo characters in ritual stories or shady pastors, and some said, wait, now it’s okay to hit other sides?

The film’s message seems to be about how intolerance shows up everywhere; tribal, religious, even within families. There’s this side story with Gosi (Effiong himself acting too) and his wife’s background clashing with his parents’ prejudices. It ties into the bigger chaos, showing division isn’t just north-south or herder-farmer. But audience perception? Split right down the middle. Some hail it as brave, finally calling out the insecurity that’s costing lives and billions in ransoms (reports from just last year put kidnappings in the thousands). Others see it as careless, potentially adding fuel to ethnic fires. And there was talk of a disclaimer, though I didn’t spot one forced by censors in the version I watched; maybe it got added quietly or debated behind scenes. If it was there, it might have softened things, but it could also feel like undermining the story’s boldness. Like, if you’re going to tackle this, own it fully; a disclaimer saying “fiction, not real groups” might protect legally but dull the edge.

Does a movie like this have a responsibility to tread lighter on unresolved crises? Nollywood’s always mixed entertainment with social stuff; think of older films hitting corruption or rituals. But this feels different because the wounds are fresh. Kidnappings aren’t history; they’re happening now. So yeah, maybe there’s a duty to avoid simplifying blame. At the same time, art should provoke, right? Holding back entirely means ignoring the pain of victims who’ve lost family on highways or in villages. Effiong seems to come from a place of frustration with the system; police helpless, families scrambling for cash, no real justice. The ending doesn’t wrap neat; it’s morally gray, leaving you unsettled. That might be the point, mirroring how nothing gets resolved in real life.

Shifting to the actual filmmaking, because beyond the noise, how does it hold up as cinema? Pretty solid for a debut, I’d say. The thriller parts keep you gripped; pacing starts slow with the wedding vibes, building that false security, then slams into high gear. Tension in the bush scenes is real; you feel the heat, the fear, the exhaustion. No over-the-top heroes saving the day easy. Daniel Etim Effiong directs with confidence, especially in those confined, sweaty moments where captives negotiate or turn on each other. He acts too as Gosi, carrying a lot of the emotional weight; his private worry about his wife’s health adds layers, making his desperation personal.

Genoveva Umeh as Derin brings raw vulnerability; her swings from hope to breakdown feel authentic, even if her thread fades a bit mid-film. Tina Mba delivers another strong performance as always, grounding the family side. The lesser-known actors playing kidnappers, like Ibrahim Abubakar as the tough one, add menace without caricature. Kunle Remi and others fill out the ensemble well. The script by Lani Aisida juggles multiple views; we see inside the gang, the families scrambling, even security stumbling. That multi-angle approach elevates it from straight victim story to something broader about society’s failures.

Technically, it’s a step up for Nollywood thrillers. Cinematography shifts nicely; bright, colorful wedding contrasting dark, shadowy forest. Sound design uses silence effectively, or sudden bursts, amplifying jumps. Editing keeps things tight, no dragging despite the heavy themes. Action isn’t Hollywood slick, but gritty; machetes, guns, blood spatter that feels visceral. Some reviews call it uneven, with twists you might guess or subplots that don’t fully connect. Fair enough; the social commentary sometimes crowds the narrative, making plot feel secondary at points. But it never bored me; ran about two hours, felt paced right.

Is this a landmark for Nollywood tackling tough stuff? Kind of, yeah. We’ve had films on corruption or Boko Haram edges, but this hits the herder-bandit crisis head-on, with organ trade and caste prejudice thrown in. It shows the industry can handle complexity, even if not perfectly. Not everyone will agree on the balance, but it sparks conversation; that’s something. In a time when insecurity reports keep coming (thousands kidnapped in recent years, ransoms in billions), a film like this forces us to look, even if uncomfortably.

Overall, The Herd left me thinking more about Nigeria’s fractures than any neat entertainment. It’s bold, flawed, tense, and timely. If you’re up for something that mirrors harsh realities without sugarcoating, give it a watch. Just know it might upset you; or make you argue with friends afterward. And that’s probably what the filmmakers wanted all along.